EQUINE LAMINITIS – Evidence-Based Understanding, Diagnosis and Modern Management

Laminitis is the most serious disease of the equine foot and a leading cause of chronic pain, long-term disability and euthanasia in horses, ponies and donkeys. It is widely recognised as the second most common cause of death in horses after colic. Despite significant advances in research, laminitis remains a devastating and often unpredictable condition, requiring early recognition, specialised intervention and evidence-based decision-making.

What Is Laminitis?

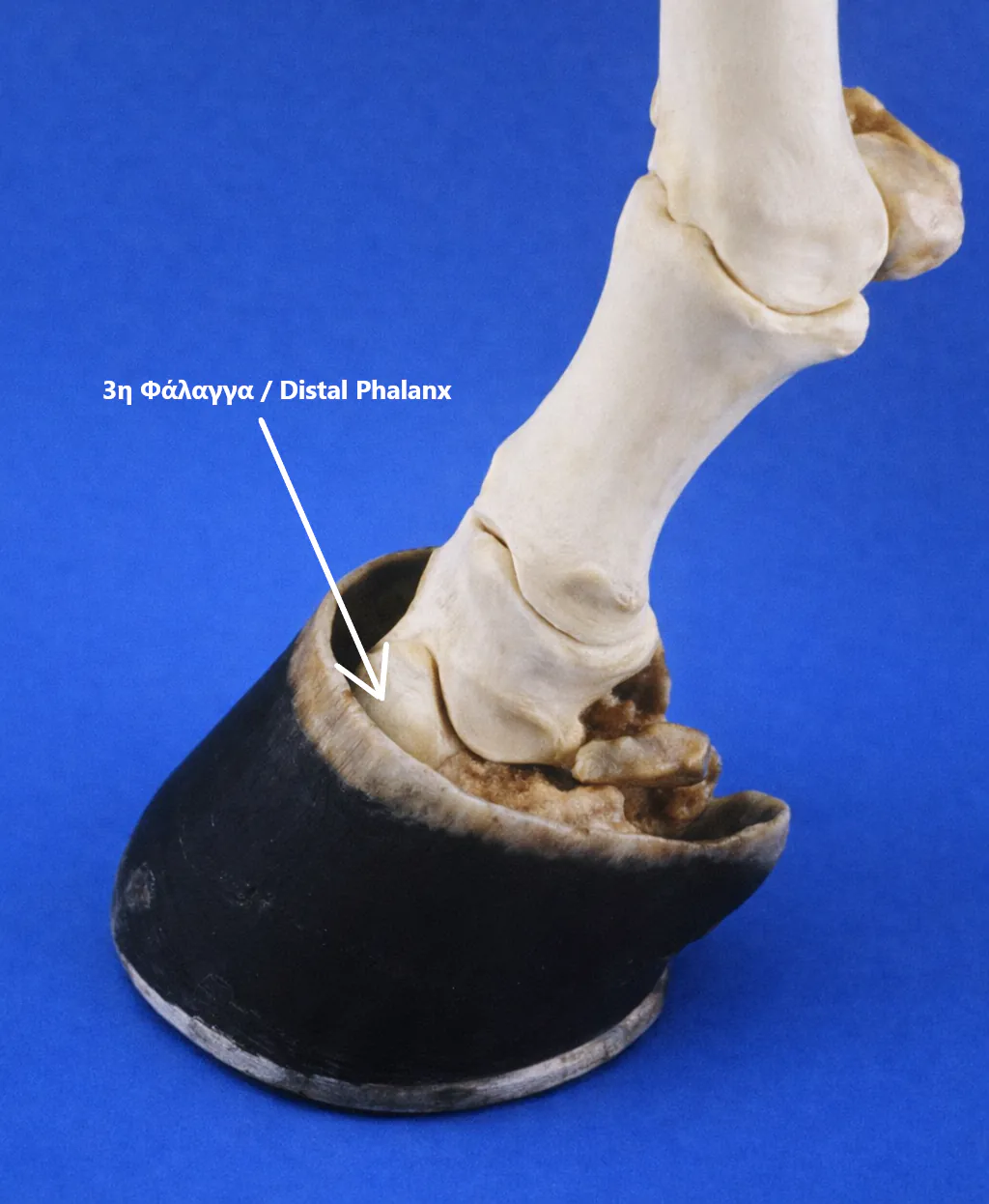

Laminitis occurs when the distal phalanx (coffin or pedal bone, P3) fails to remain securely attached to the lamellae lining the inner surface of the hoof capsule.

In the healthy horse, this attachment forms a highly specialised suspensory apparatus. The inner hoof wall is folded into microscopic, leaf-like structures (lamellae) that increase surface area and allow strong yet flexible load distribution.

When lamellar failure occurs, the weight of the horse and the forces of locomotion drive the distal phalanx downward or cause it to rotate within the hoof capsule. In severe cases, this displacement may result in penetration of the sole by the distal phalanx. The associated vascular compromise, tissue damage and inflammation lead to severe, unrelenting pain and characteristic lameness.

Laminitis is frequently recurrent and can result in permanent anatomical and functional changes to the foot.

Pathophysiology and Disease Impact

Once lamellar integrity is lost:

✓ Arteries and veins are crushed and sheared.

✓ The corium of the sole and coronet is damaged.

✓ Inflammation and ischemia perpetuate tissue injury.

✓ Mechanical instability progresses.

By the time a horse presents with severe clinical signs (Obel grades 3–4), extensive lamellar damage and displacement of the distal phalanx are often already present, particularly in endocrinopathic laminitis. This explains why delayed intervention so frequently results in poor outcomes.

Types and Predisposing Factors

Laminitis is not a single disease entity.

Major categories include:

✓ Endocrinopathic Laminitis

Associated with Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) and Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID). These horses may not appear systemically ill, and laminitis may be the first obvious clinical sign.

✓ Sepsis-Related Laminitis

Occurs secondary to systemic inflammation, endotoxaemia or severe infection.

✓ Supporting Limb Laminitis

Develops when excessive weight is borne on one limb due to injury or disease of the opposite limb.

Understanding the underlying cause is essential, as treatment priorities, prognosis and preventive strategies differ significantly.

Clinical Presentation

Acute laminitis is characterized by:

✓ Sudden onset lameness.

✓ Increased hoof temperature.

✓ Bounding digital pulses.

✓ Painful withdrawal response to hoof testers.

Chronic laminitis presents with varying degrees of:

✓ Hoof capsule distortion.

✓ Divergent growth rings.

✓ Altered sole depth and contour.

✓ Persistent or intermittent lameness.

Diagnosis may be straightforward in acute severe cases but considerably more challenging in chronic or mild cases, especially in older horses with concurrent orthopedic disease.

Diagnosis: Clinical Examination, Radiography and Blood Tests

Laminitis cannot be responsibly diagnosed or managed based on clinical signs alone.

Radiography is essential to:

✓ Confirm the presence of laminitis.

✓ Determine the degree and type of distal phalanx displacement.

✓ Guide trimming and shoeing decisions.

✓ Monitor disease progression and treatment response.

Venography is a highly valuable tool for the diagnosis and treatment of laminitis, as it allows assessment of vascular damage in the hoof before changes become evident on conventional radiographs. Its value is greatest when performed at the onset of the disease, as it reveals the level of damage that has already occurred and helps guide the selection of the appropriate therapeutic strategy.

Equally important, yet still underestimated in some clinical settings, is the role of blood testing.

Even though blood tests are very important for diagnosing and managing laminitis, in some veterinary practices they are still not used as often as they should be. This may be due to outdated beliefs or lack of awareness, but performing the right blood tests can make a big difference in protecting your horse and preventing further episodes.

Clinical examination, radiography and laboratory testing are complementary tools, not alternatives.

Treatment Principles: Individualised, Not Formulaic

The immediate goal in acute laminitis is stabilisation of the distal phalanx, regardless of the degree of displacement.

Trimming and shoeing must be radiographically guided and tailored to the individual horse. There is no universal “laminitis shoe.”

The biomechanical objectives of hoof care include:

✓ Altering the centre of pressure.

✓ Redistributing load-bearing forces.

✓ Reducing impact shock.

✓ Facilitating breakover.

✓ Protecting damaged structures.

Horses with dorsal rotation present very different mechanical challenges from those with distal displacement (sinking), and management must reflect these differences.

Common Myths and Dangerous Misconceptions

Myth: “Horses with laminitis should be walked to improve circulation.”

✓ True: This belief persists despite clear scientific evidence to the contrary.

Forced exercise and walking are CONTRAINDICATED in acute laminitis. Movement increases mechanical stress on already compromised lamellae, exacerbating displacement and pain. Horses with painful laminitis require strict box rest, deep bedding and minimal movement.

Myth: “All laminitic horses require the same type of shoe.”

✓ True: Laminitis is a biomechanical disease with multiple presentations. Applying a single shoeing method to all cases is inappropriate and potentially harmful.

Myth: “Sedatives such as acepromazine improve blood flow to the hoof and therefore treat laminitis.”

✓ True: Although acepromazine can increase blood flow in larger digital vessels, scientific studies have shown that it does not improve blood flow within the lamellae themselves. Consequently, acepromazine should not be considered a treatment for laminitis, nor a means of protecting the lamellae. Effective laminitis management relies on mechanical stabilisation, strict rest and addressing the underlying cause—not pharmacological vasodilation.

Medical and Advanced Therapeutic Options

✓ Cryotherapy

A proven preventive strategy in horses at high risk of developing laminitis.

✓ Deep Digital Flexor Tenotomy

Remains the most cost-effective salvage procedure in severe or non-responsive cases.

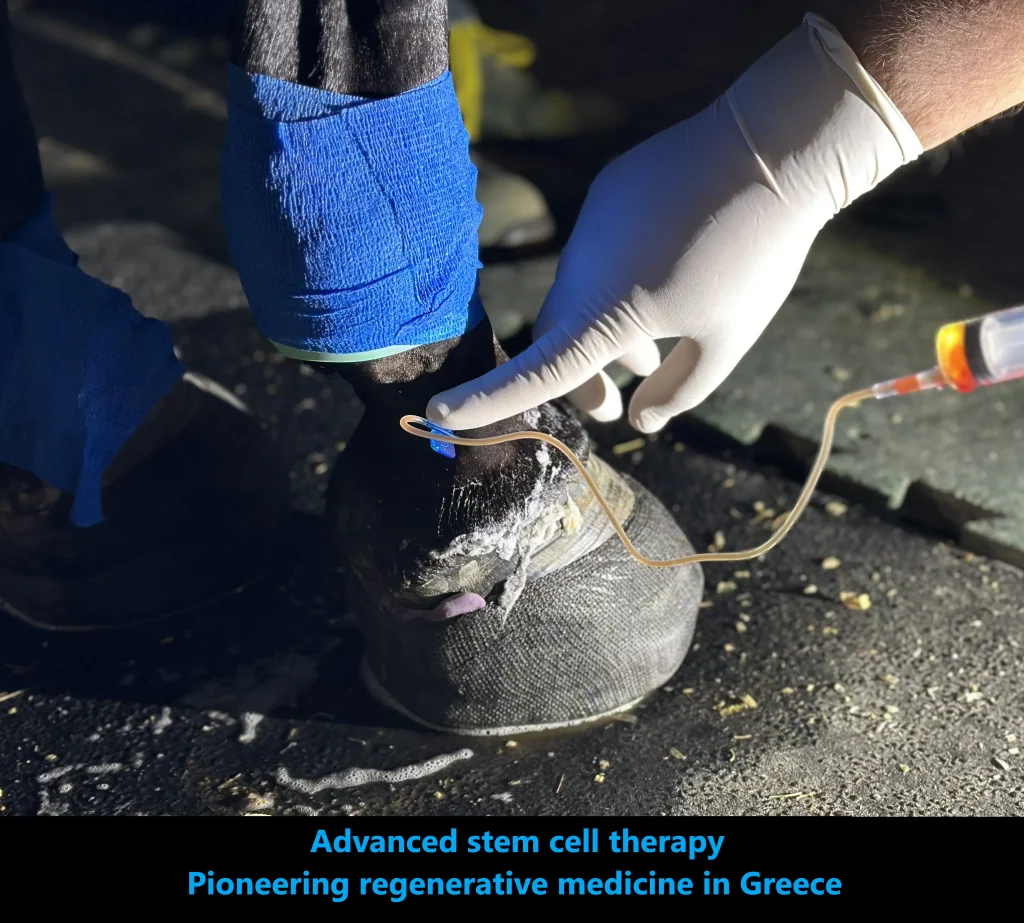

✓ Stem Cell Therapy

Used as an adjunctive treatment, stem cells have shown promising clinical results in selected laminitic patients.

✓ Corticosteroid Use

Current evidence does not demonstrate an association between intrasynovial corticosteroid injections and laminitis in horses without concurrent risk factors, although high-quality data remain limited.

In addition to these advanced therapies, standard medical treatment includes pain management using NSAIDs, supportive care such as deep bedding, dietary control, and careful monitoring. These measures remain fundamental but are generally well established and not controversial.

Prognosis and Recovery

Recovery from laminitis typically requires weeks to months.

Published studies indicate that:

✓ Approximately 72% of horses are sound at the trot after eight weeks.

✓ Around 60% return to work.

Outcome depends on severity at diagnosis, speed of intervention, underlying cause and the quality of mechanical and medical management.

Conclusion

Laminitis is not merely a hoof disease. It is a complex, multifactorial condition requiring:

✓ Thorough clinical evaluation.

✓ Radiographic assessment.

✓ Appropriate laboratory testing.

✓ Individualised mechanical and medical treatment.

Outdated dogma and oversimplified approaches continue to compromise outcomes.

At Hippiatric Care, laminitis is managed through evidence-based medicine, interdisciplinary collaboration and a commitment to treating both the foot and the horse.

References:

- Australian Government. Equine Laminitis: Current Concepts.

- Bailey, S.R., & Eades, S.C.Vasoactive Drug Therapy. In: Equine Laminitis, Chapter 32.

- Baxter, G.M. (Ed.). Lameness in Horses, 7th Edition. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Belknap, J.K., & Kames, J. Equine Laminitis.

- Eastman S, Redden RF, Williams CA. Venograms for Use in Laminitis Treatment. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 32(11):757–759, 2012.

- Morrison, S., Dryden, V.C., Bras, R., Morrell, S. How to Use Stem Cells in Clinical Laminitis Cases.

- O’Grady, S.E., DVM, MRCVS – Publications on farriery and laminitis biomechanics.

- Royal Veterinary College (RVC), University of London – Equine Laminitis Resources.

- Tokawa, P.K.A., Baccarin, R.Y.A., Zanotto, G. (2023). Systematic Review of the Association Between Intrasynovial Corticosteroid Use and Laminitis—What Is the Evidence?